Music Sunday with the Community Chorus – May 14

[Click here for downloadable PDF of the following content]

[Click here for downloadable PDF of the following content]

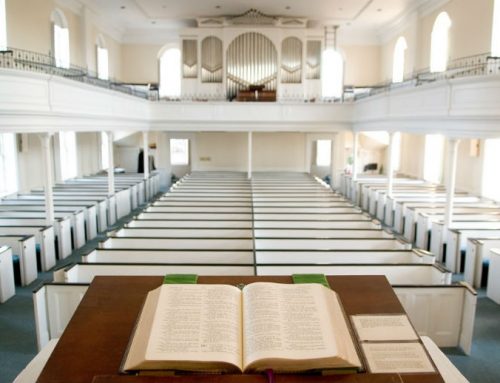

On Music Sunday this year we celebrate the 325th Anniversary of the Presbyterian Church of Lawrenceville. The Lawrenceville Community Chorus sings works of Ira Randall Thompson (1899-1984) and Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990).

Randall Thompson’s father was head of the English Department at The Lawrenceville School, both he and his brother were educated there and graduated in 1916. His parents were the Housemasters for Cleve House, and Randall spent his formative years growing up in the shadow of PCoL. His first attempts at composition began around 1915 with a piano sonata and a Christmas partsong. The Thompson brothers are listed on the PCoL “Roll of Honor” outside of the Meethinghouse door along with the names of the other men from this congregation who served during WWI. Thompson’s family worshiped here at PCoL and Randall was known to have played the organ in the church on several occasions. When the regular organist at PCoL became ill, Randall was offered the position, however, his parents would not let him accept.

After returning from the war he went on to study at Harvard University, where he auditioned for the chorus but was turned down by its conductor, Archibald T. Davison, who eventually became his mentor. Thompson later mused, “My life has been an attempt to strike back.” His early works, including several songs, varied considerably in style. But in 1922 he began studies at the American Academy in Rome where, inspired by the master composers of the Renaissance, he developed the musical style which led him to the forefront of American choral composers. During his career he intermingled both teaching and composing, having been director of the prestigious Curtis Institute of Music as well as a professor at his alma mater, Harvard University. Though he composed symphonies, songs, operas and instrumental works, he is best known for his choral compositions. He is known as the “Dean of American Choral Music”.

The choir will sing three of his well known anthems:

The Last Words of David

Commissioned and premiered in 1949 by the Boston Symphony Orchestra to honor Dr. Serge Koussevitsky for 25 years of directorship. Roaring ascending scales in the accompaniment reflect the great strength of this Old Testament text from II Samuel 23: 3,4. The popularity of this anthem is surpassed only by Thompson’s “Alleluia”.

The Best of Rooms

Composed in 1963, this American choral classic features words from Christ’s Part (1647) by Robert Herrick (1591-1674). Complete text: “Christ, He requires still, wheresoe’er He comes, To feed, or lodge, to have the best of rooms; Give Him the choice; grant Him the nobler part Of all the house: the best of all’s the heart.”

The Lord is my Shepherd (Psalm 23)

Commissioned in 1962 in memory of Dorothy C. Drake, Head of the Music Department of the Chapin School, New York City. It was first performed by the Chapin School Choral Club in 1964 under the direction of the composer.

Leonard Bernstein was one of Randall Thompson’s students both at Harvard and at Curtis, according to his own testimony in a speech he gave at Curtis Institute’s 75th Anniversary Banquet.

Bernstein is probably the most famous American musician of the twentieth century. He was known for composition, conducting and teaching. His personality was larger than life, and he was a media sensation throughout his career.

Chichester Psalms

“Commissioned by the Very Rev. Walter Hussey, Dean of Chichester Cathedral, Sussex, for its 1965 Festival, and dedicated, with gratitude, to Cyril Solomon”

In 1965, Leonard Bernstein took a sabbatical from his post as Music Director of the New York Philharmonic. Freed from the time-consuming obligations of conducting and studying scores, he could now turn his attention to composition. His objective during this conducting hiatus was to compose a Broadway musical based on Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth, in collaboration with director/choreographer Jerome Robbins, with book and lyrics by Betty Comden and Adolph Green. Bernstein outlined his concept in a poem he submitted to the New York Times on October 24, 1965:

But not to waste: there was a plan,

For as long as my sabbatical ran,

To write a new theater piece.

(A theater composer needs release,

And West Side Story is eight years old!)

And so a few of us got hold

Of the rights of Wilder’s play The Skin of Our Teeth

This turned out to be a challenging time for the composer. In Working with Bernstein, Jack Gottlieb quotes a letter written on November 29, 1964: “Skin is stalled. Life, this agonizing November, is a tooth with its skin stripped off. I don’t know what I’m writing. I don’t even know what I’m not writing… I can’t get over Kennedy or Marc. Life is a tooth without a skin.” The assassination of President Kennedy had occurred a year earlier, and Bernstein’s close friend, the composer Marc Blitzstein, had been murdered in January of that year. Ultimately, the collaboration fell through. In a letter to the composer David Diamond, Bernstein described himself as “a composer without a project.”

In early December 1963, Bernstein received a letter from the Very Reverend Walter Hussey, Dean of the Cathedral of Chichester in Sussex, England, requesting a piece for the Cathedral’s 1965 music festival: “The Chichester Organist and Choirmaster, John Birch, and I, are very anxious to have written some piece of music which the combined choirs could sing at the Festival to be held in Chichester in August, 1965, and we wondered if you would be willing to write something for us. I do realize how enormously busy you are, but if you could manage to do this we should be tremendously honoured and grateful. The sort of thing that we had in mind was perhaps, say, a setting of the Psalm 2, or some part of it, either unaccompanied or accompanied by orchestra or organ, or both. I only mention this to give you some idea as to what was in our minds.” The festival united the cathedral choruses of Chichester, Winchester and Salisbury. Dr. Hussey was a noted champion of the arts, having commissioned works by visual artists, poets, and composers. Among these are: an altarpiece painted by Graham Sutherland, stained glass windows by Marc Chagall, a sculpture depicting the Madonna and child by Henry Moore, a litany and anthem by W.H. Auden, and perhaps most notably, the cantata Rejoice in the Lamb by Benjamin Britten. Despite Dr. Hussey’s initial wish for the setting of Psalm 2, Bernstein responded with a “suite of Psalms, or selected verses from Psalms,” under the working title, Psalms of Youth (Bernstein changed the title because it misleadingly suggested that the piece was easy to perform). Hussey was hoping that Bernstein would feel unrestrained for composing in a more popular vein despite the sacred nature of the assignment. Hussey wrote, “Many of us would be very delighted if there was a hint of West Side Story about the music.”

Bernstein composed Chichester Psalms amid a busy schedule, completing his first work since the Third Symphony, Kaddish, in 1963, written in memory of President Kennedy. Both pieces combine choruses singing Hebrew text, with orchestral forces, but where Kaddish is a statement of profound anguish and despair, Chichester Psalms is hopeful and life-affirming.

Unlike a good portion of the music he composed (but did not complete) during his sabbatical, Chichester Psalms is firmly rooted in tonality. Bernstein commented during a 1977 press conference, “I spent almost the whole year writing 12-tone music and even more experimental stuff. I was happy that all these new sounds were coming out: but after about six months of work I threw it all away. It just wasn’t my music; it wasn’t honest. The end result was theChichester Psalms which is the most accessible, B-flat majorish tonal piece I’ve ever written.” Again, from the poem submitted to the Times:

For hours on end I brooded and mused

On materiae musicae, used and abused;

On aspects of unconventionality,

Over the death in our time of tonality…

Pieces for nattering, clucking sopranos

With squadrons of vibraphones, fleets of pianos

Played with the forearms, the fists and the palms —

And then I came up with the Chichester Psalms.

… My youngest child, old-fashioned and sweet.

And he stands on his own two tonal feet.

Chichester Psalms juxtaposes vocal part writing most commonly associated with Church music (including homophony and imitation), with the Judaic liturgical tradition. Bernstein specifically called for the text to be sung in Hebrew (there is not even an English translation in the score), using the melodic and rhythmic contours of the Hebrew language to dictate mood and melodic character. By combining the Hebrew with Christian choral tradition, Bernstein was implicitly issuing a plea for peace in Israel during a turbulent time in the young country’s history. Each of the three movements of Chichester Psalms contains one complete Psalm plus excerpts from another paired Psalm. Musically, Bernstein achieved Dr. Hussey’s wish for the music to remain true to the composer’s own personal style. The piece is jazzy and contemporary, yet accessible. In a letter to Hussey, Bernstein characterized it as “popular in feeling,” with “an old-fashioned sweetness along with its more violent moments.”

The first movement begins with a triumphal introductory phrase with text from Psalm 108 (“Awake, psaltery and harp!”) that draws on the interval of a minor seventh (a significant musical motive that returns in the final movement, engendering a cyclical form). This dramatic introduction prompts a vigorous and bright, scherzo-like dance in 7/4 meter of Psalm 100 (“Make a joyful noise until the Lord”). The number seven is an important number in Gematria (Hebrew numerology) and features prominently in the composition of the Chichester Psalms, both in the rhythmic structure and the harmonic/melodic language of the music.

A gentle and lyrical setting of Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd”) opens the second movement, featuring a soloist (eventually joined by soprano voices) with harp accompaniment, a musical evocation of King David, the shepherd-psalmist.

Bernstein created this melody using material from The Skin of Our Teeth. The bitter expression and agitated music of Psalm 2 (“Why do the nations rage”) interrupts this tranquility. At this, the most dramatic moment of the composition, the setting prominently features music cut from West Side Story. Though the upper voices return with the soloist’s song of faith, the tension of suppressed violence lingers throughout the rest of the movement.

The third and final movement is the longest of the piece; its opening section features a more dissonant and rigorous compositional style than the others. With a fiery and elegiac introduction played by the strings, the music recalls the minor seventh figure, the musical motive from the first movement. In a moment of consolation, the orchestra is abruptly hushed for a simple, unsentimental presentation of Psalm 131 (“Lord, Lord, my heart is not haughty”), a rocking lullaby in 10/4. Psalm 133 (“Behold how good”) comprises the coda material, predominantly in the style of a Lutheran chorale, significant for being the only moment in the entire composition for solo chorus, without instrumental accompaniment. Constructed from the work’s opening musical motive, the music and text combine in a visionary plea for reconciliation and unity throughout the world before concluding in a final Amen.

Chichester Psalms is tuneful, tonal and contemporary, featuring modal melodies and unusual meters. Through its use of motivic repetition, there is the sense of a hallowed rite. From the time of its sold-out world premiere at Philharmonic Hall on July 15, 1965 conducted by the composer himself, it was apparent that Bernstein had created a magically unique blend of Biblical Hebrew verse and Christian choral tradition; a musical depiction of the composer’s hope for brotherhood and peace. Today you will hear the version orchestrated by Bernstein himself for organ, 1 percussionist and harp.